Creating State Machines

Creating state machines is a valuable engineering task. While you do it, you understand gradually more of your system and the task it should solve. Usually, this is difficult in the beginning but gets easier as you learn more. In some cases it may also happen that you need to start over, because you have understood, for example, that it is easier to model some behavior with a set of state machines instead of a single one. This will get much better with some experience. But it is not always difficult. Often, you manage to handle a problem after some attempts and then you "see" that you have a good solution. In that respect, state machines are very nice, because a problem, once modelled properly, can be easily checked by executing the state machines.

State machines are precise artefacts that can take care of the detailed behavior, so they are suitable for unambiguously define how a system should work. In the end, you did a good job if you are able to map user requirements to a set of consistent, high-quality state machines.

With high quality, we mean here that:

- The state machine is syntactically correct.

- The state machine describes behavior that makes sense and is clearly defined.

- The state machine has a good layout that conveys how it works and helps the reader to understand it.

- The state machine can be implemented in code.

How to get started, when your paper or editor is empty in the beginning? It can actually be hard to create a state machine from scratch, also for experts. Actually, I think I have never observed that even experts write down a state machine correctly on the first attempt, because there is always something that you forget. So, they key to creating a state machine: Don't even try to make it correct on the first attempt, but approach it iteratively. Sometimes it is a good idea to separate the task of creating something from the test of validating it. Otherwise it is easy to get stuck. So for state machines, we switch between writing down a state machine and then checking it.

Writing Down a State Machine

To create down a state machine, don't ba afraid to just sketch a first version. The following tips may help:

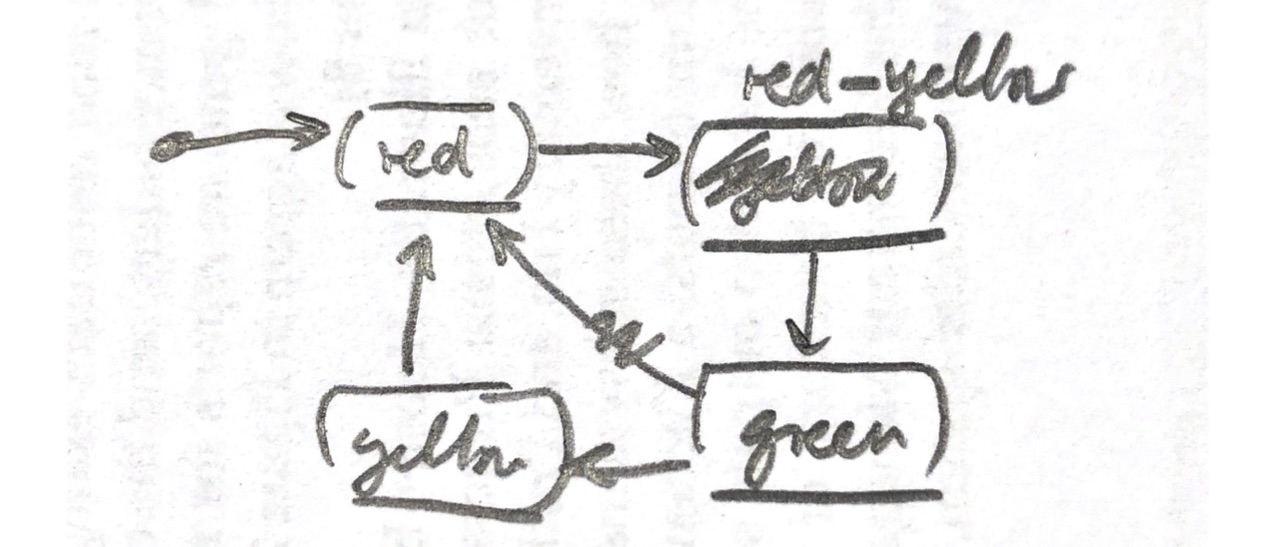

- Start with pencil and paper. Sometimes it is easier to explore design when you work alone, very focused and only with pencil and paper, where you can quickly sketch some states and transitions, without the pressure to make it work completely immediately. I have lots of experience in designing state machines. I still start with pencil and paper each time, before I go over to an electronic editor.

- Identify all triggering events. Identify and write down all kinds of events that can trigger a transition in the state machine. Make a list of all incoming messages you may react to, and all timers that are necessary. Often these triggers are determined by the problem to solve.

- Identify all actions. Make a list of all actions that are used by your state machine to achieve its purpose. In this course, we use actions that we can use in Python.

- Identify any messages to send. If the state machine communicates with another one, you should list all messages it may send to the other machine, which you can treat just like an action. Note that all messages to receive is already included in the list of triggers above.

- Introduce one state after the other, and try to map states to states of whatever your state machine describes. Sometimes, some states are quite obvious, like the states of a lamp, which are

onandoff. Sometimes, you discover that your problem has actually more states than you initially thought. For example can an electronic door lock have more than the obvious stateslockedandunlocked. The lock may beengagedmeaning that it can be potentially opened, but if the user does not open it, it goes back into itslockedstate. Working with the problem will reveal this. - Identify a default state. For some problems, it may help to think of a default state that the state machine should be in. It may then be easier to explore the other states based on this. For example, think of a doorlock. It may be easier to design a state machine for it when you start thinking of it being locked first when the system starts, and then think what should happen to open it.

- Explore the problem. Most likely, you will explore the problem and find out that you haven't understood everything, or that there are details that you have overlooked in the beginning. Be aware of what you learn, and how you can represent it with states and transitions. he state machine challenges you to learn more about the system.

- Start fresh. When you get completely stuck, throw your sketch away and start fresh.

Checking State Machines

Once you have a state machine, even a partial one, you can check if it can actually work.

For each of its states, you should check:

- Initial state? Make sure the state machine has an initial state. Otherwise, we don't know where to start.

- Are all states reachable? This means, can you start at the initial state and from there reach any of the other states by following a sequence of events? Or are there some states that you can never reach? Obviously, that must be a mistake, because if these states are not reachable, what's the point in having them? Din the missing transitions towards these states and try again.

- Is there a deadlock? This means, is there a state from which you cannot find out way out, for instance to a final state that terminates the machine? If there is a state that you cannot leave anymore, is that intended by the application?

- Are all possible events handled? In each state, did you think of any events that may arrive? Remember, that events arriving at the head of the queue and that are not executed in the form of triggers are discarded, that means, thrown away. Check if you have missed some!

- Are triggers clear? A state must not have two or more outgoing transitions that declare the same triggering event and also the same guard. This means, when an event occurs, it must be clear which transition will be chosen.

- Consume, defer or discard. Make sure that for each state, an event is either consumed (by an outgoing transition) or deferred. If a state says nothing about an event, the event is implicitly discarded in case it arrives. A state must not defer an event that also triggers one of its outgoing transitions.

For each transition you should check:

- Does every transition have a triggering event? This means that every transition must declare a trigger in the form of a message reception, a timer expiration, unless it is an initial transition or following a choice pseudo state.

- Do transitions with choice states block? Decisions must not block, which means that one of the outgoing branches of a choice state must have a guard that is

True. The safest way to achieve this is by letting one of the outgoing branches have anelsebranch.

For each timer you should check:

- Are timers properly started? All timers must be started by the machine itself, so a timer that is not started will never expire and is hence not useful. Find a proper place to start it, either as part of a transition effect or as entry or exit actions, just like other actions.

- Are timer expirations handled? Check what happens when a started timer expires. If a timeout happens in a state that does not declare an outgoing transition triggered by it, it is simply ignored. This may be okay in your machine (because something else happened and you don't need the timer anymore), but it can also be the sign of an error.

For each event you should check:

- Are all events that you need to receive handled, and are they properly handled (consumed, deferred or discarded) in each state? Are there events that are never handled?

These are the rules that you can check even without knowing exactly what the application should do, just by looking at the state machines. These are generic rules, independent of a specific application, and if they don't hold, it is very likely that you do have a problem. But then there are also errors that have to do with your specific application. This can be a bit harder to find out. You need to simulate the state machines using your fingers and go through it state by state and event by event. When the problem is not too big, this is possible. Later, once we implement state machines in Python, you will also be able to build functioning prototypes, which you can use and test to see how the final state machine behaves.