Event Orderings and Semantics

Let's have a closer look at the semantics of sequence diagrams, that is, what they mean in detail. We do this by looking at the detailed events that happen as part of an interaction. Understanding in which order they are supposed to happen, means to understand what the interaction really means.

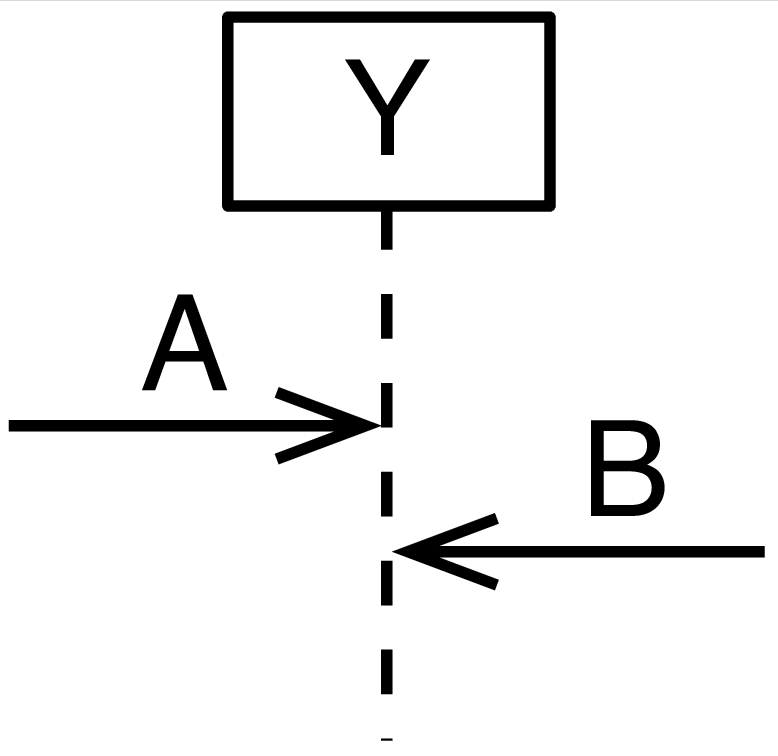

The passing of a message A consists of two events:

-

The message is sent, written as !A.

-

The message is received, written as ?A.

Ordering Rule 1: Because our universe seems to act causally, a

message must be sent before it can be received. For a message A, the

only sequence of events that is possible is <!A, ?A>.

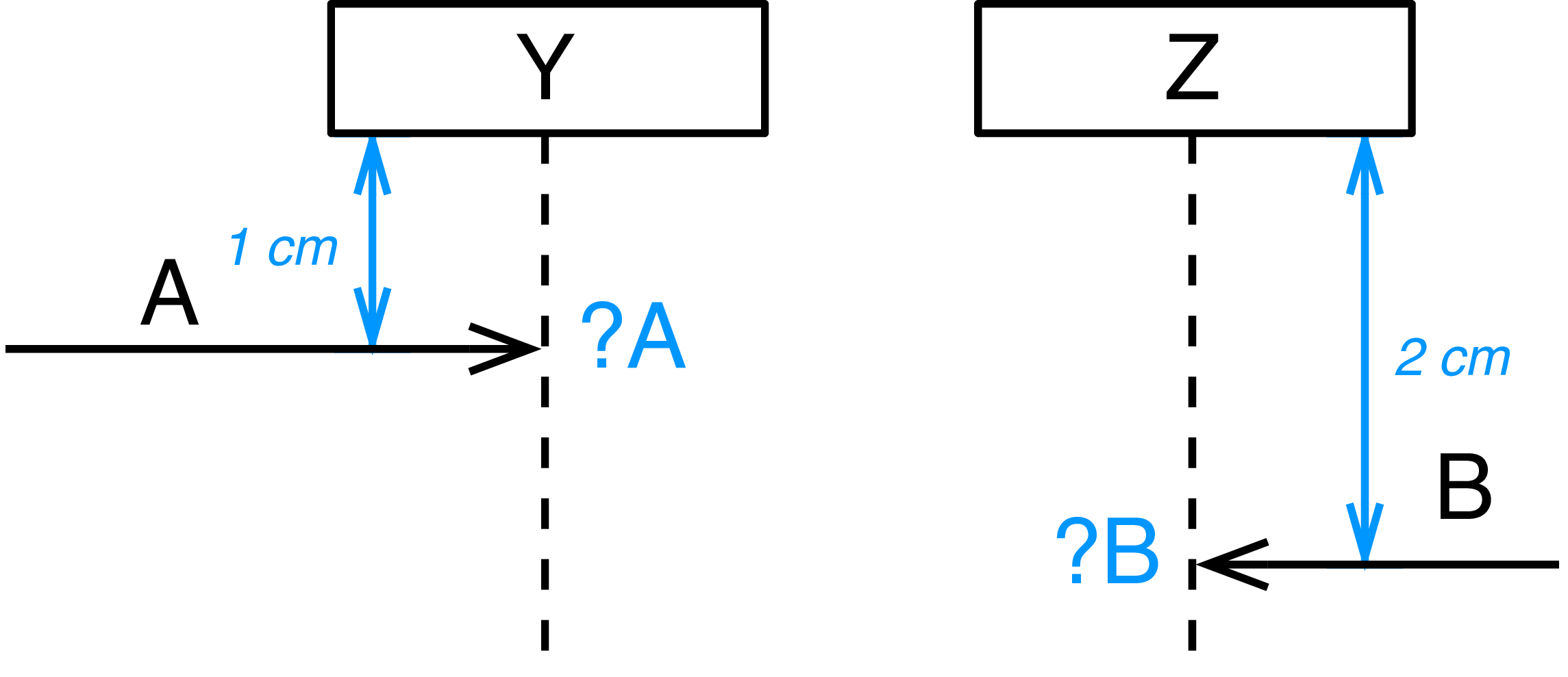

Ordering Rule 2: A second ordering rule is that of lifelines:

Events along the same lifeline are in a total order. Below, this

means that lifeline Y receives signal A before it receives B,

< ?A, ?B >.

Now comes the part that may be less intuitive: Events on different lifelines are not ordered, even though they have distinct y-coordinates. In the diagram below, the reception of A and the reception of B are clearly at different y-coordinates. Visually, A happens before B. But this is not an order that the diagram implies. Because these events are not related with each other, the diagram does not tell if any of them happens before each other, despite it may look like it.

For some, this non-ordering of events on different lifelines may not be

intuitive at the first glance. The following illustration may help you

to understand it: Imagine that the events along a lifeline are connected

to it by rings. The rings can move up and down along the lifeline, and

the message can get a different slope depending on the position on the

rings. Rings attached to the same lifeline cannot pass each other.

Therefore, the diagrams below all look different, but imply the same

ordering among the events, irrespective of their absolute position on

the lifelines. What counts is that A is received before B, and this

does not change in any of the diagrams.

The slope of messages is hence only a means of illustration. A recommendation is to use horizontal messages where possible, and messages with a downwards slope when you want to show that messages cross each other. (That comes later.) Avoid messages with an upwards slope.

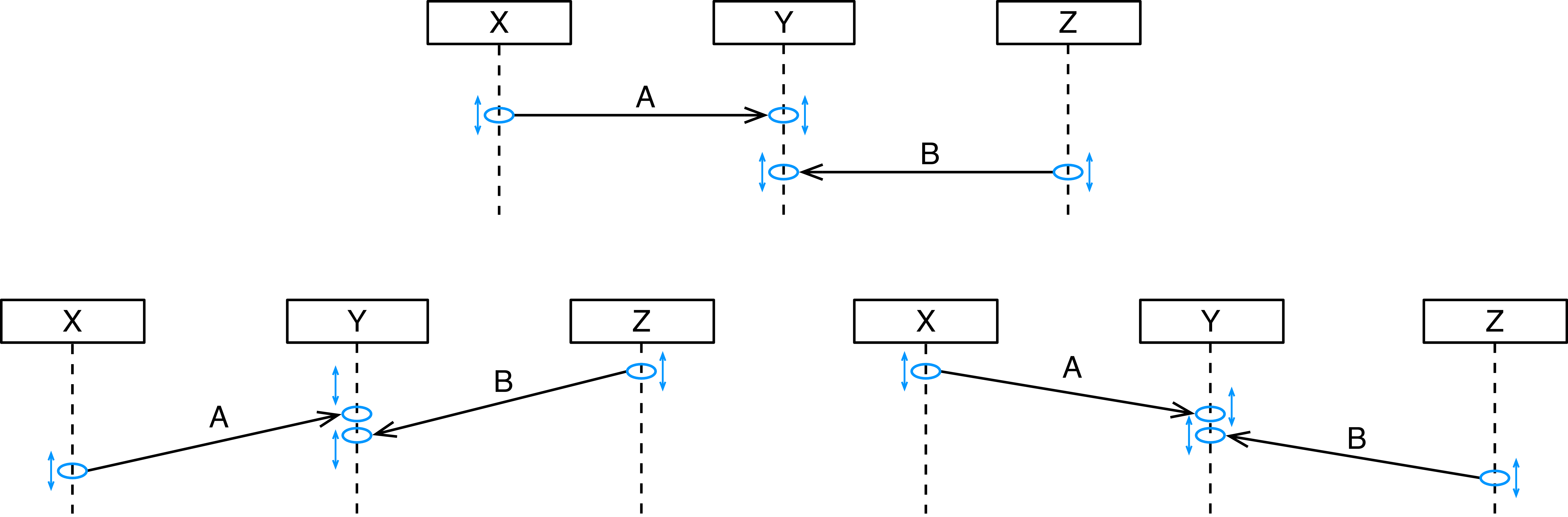

The example below shows a sequence diagram with two messages, and four distinct events:

Intuitively, we already know one sequence in which these events can

happen, that is, we know that <!A,?A,!B,?B> is one valid

trace. However, it is not the only possible trace. To find the other

traces, we may start by writing down all possible different combinations

we can get from these events. With 4 events, we end up with 24 different

traces:

< !A,?A,!B,?B >, < !A,?A,?B,!B >, < !A,!B,?A,?B >, < !A,!B,?B,?A >, < !A,?B,?A,!B >, < !A,?B,!B,?A > < ?A,!A,!B,?B >, < ?A,!A,?B,!B >, < ?A,!B,!A,?B >, < ?A,!B,?B,!A >, < ?A,?B,!A,!B >, < ?A,?B,!B,!A > < !B,!A,?A,?B >, < !B,!A,?B,?A >, < !B,?A,!A,?B >, < !B,?A,?B,!A >, < !B,?B,!A,?A >, < !B,?B,?A,!A > < ?B,!A,?A,!B >, < ?B,!A,!B,?A >, < ?B,?A,!A,!B >, < ?B,?A,!B,!A >, < ?B,!B,!A,?A >, < ?B,!B,?A,!A >

< !A,?A,!B,?B >,

< !A,?A,?B,!B >,

< !A,!B,?A,?B >,

< !A,!B,?B,?A >,

< !A,?B,?A,!B >,

< !A,?B,!B,?A >

< ?A,!A,!B,?B >,

< ?A,!A,?B,!B >,

< ?A,!B,!A,?B >,

< ?A,!B,?B,!A >,

< ?A,?B,!A,!B >,

< ?A,?B,!B,!A >

< !B,!A,?A,?B >,

< !B,!A,?B,?A >,

< !B,?A,!A,?B >,

< !B,?A,?B,!A >,

< !B,?B,!A,?A >,

< !B,?B,?A,!A >

< ?B,!A,?A,!B >,

< ?B,!A,!B,?A >,

< ?B,?A,!A,!B >,

< ?B,?A,!B,!A >,

< ?B,!B,!A,?A >,

< ?B,!B,?A,!A >Because of the ordering rules from above, not all of these traces are possible. The sequence diagram Alpha from above relates the four events with each other.

-

Because of message ordering, we know that only those traces are valid ones, in which a signal is sent before it is received. This means,

!Amust happen before?Aand!Bmust happen before?B. -

Because of lifeline ordering, we also know that those traces, in which events do not follow the order of the lifeline, are invalid. This means

!Amust happen before!B, and?Amust happen before?B.

Exercise: Can you find the traces that violate any of the two ordering rules, and strike them out?

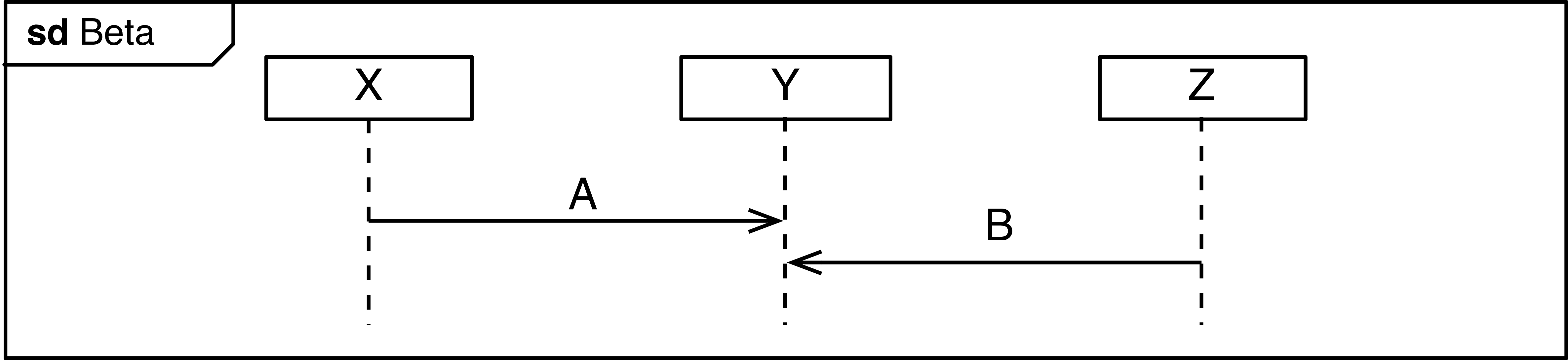

Co-Regions

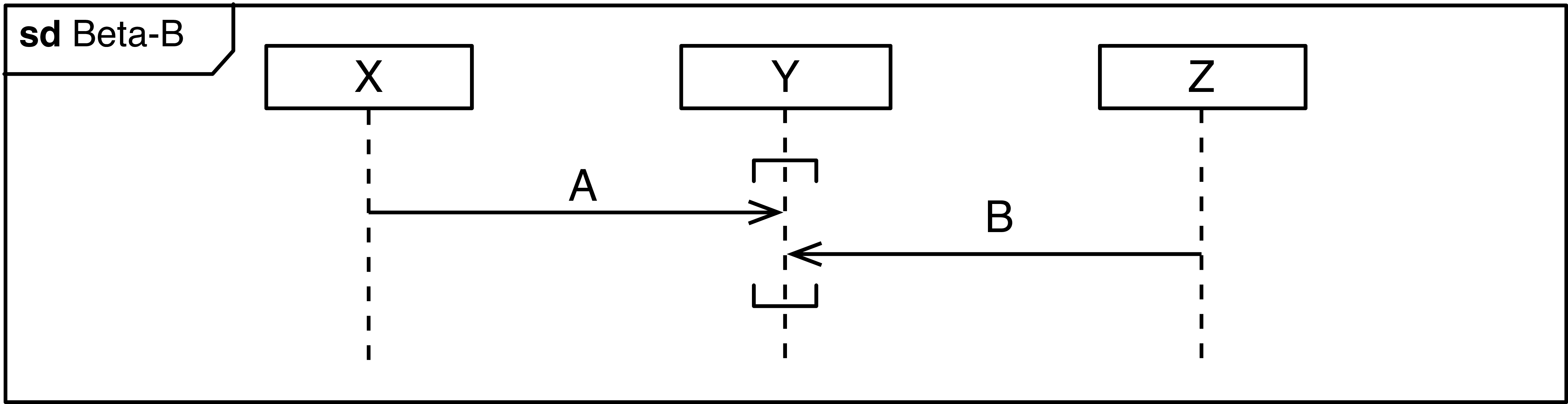

The diagram Beta below only covers the scenario that A is received

by Y before B.

Exercise: Write down all the possible traces that the sequence diagram Beta allows.

In reality, it will be hard or impossible to ensure that this order is

maintained, especially since the diagram allows to send B first. For a

real and robust specification, we should handle such situations. One way

is to demand from component Y that it must be prepared to properly

handle the arrival of messages A or B in any order. For that, we

can use a so-called co-region. These are the brackets placed on the

lifeline Y. Within the brackets of a co-region, events on the lifeline

are not ordered anymore, i.e., they can happen in any order.

Exercise: Which are the additional traces that are possible, if

the events within the co-region (?A and ?B) can happen in any order?

Exercise: Is there a way to handle the situation also in another way? For instance, can you, just by adding a message (and without a co-region), reduce the number of traces so that there is only one possible trace left for diagram Beta-C?