Components

What are Components?

Surprisingly, there is not a single definition for the concept of components. Martin Fowler calls the term on its own as "semantic free", allowing all types of interpretation, and a book on components offer various definitions, but is also open about that there is not a fixed definition that satisfies everyone.

For the following, you can just think of components as pieces of software that can be combined together ("composed") to create the entire software of our system.

To give you a more specific idea, you can think in our case of components as a set of classes or code libraries with a set of interfaces so that they can communicate with other components. Some of the code may realize STMPY state machines, and other code may do other stuff.

Components clearly focus on the implementation of the system. Hence they serve often several use cases, and one use case requires usually the effort of several components. That means, while we struggled with the use cases to structure the system according to the user's perspective and the requirements, the components structure the implementation of it.

Why Do We Need Components?

So far in the course, we have considered small examples and focused on single state machines that controlled some behavior, like the Headlamp, the Car Lock Controller and the Airport Gate Controller. For a realistic system, we cannot just deploy a single state machine, or a single file with some code. Here are just a few reasons that you may instantly agree with:

- Since most systems are distributed, we need to create different parts of the software for the different locations that can be deployed and started on their own.

- It is also likely that we want to use some existing code or even larger parts of the system that we get from elsewhere. This again makes it necessary to split the implementation into parts.

But even if we wrote all our code ourselves and new for each new system (good luck with that), and even if the system wouldn't be distributed, we need to decompose the system implementation into smaller parts to keep it manageable at all. Hence, it is not a question if we should partition our system into parts, but rather how.

Components and Classes Are Not the Same

Maybe you think "Isn't this what objects and classes are for?" But that doesn't quite fit. Individual objects are not deployed in a system, they are often too fine-grained.

You may well think of components as "objects" in terms of "things". And internally, when using an object-oriented language, they are built from classes and objects. (They may even extend a class Component provided by some component framework.) So if you want to think in object-oriented terms, think of a component as a set of classes and objects assembled into something bigger, with some extra properties that we look at in the following.

Component-Based Software Engineering

Working with components is not just about the components and how they are constructed and what they contain. To create components also means to partition the entire system into components. This requires good overview of the system, and may result in hard choices about its architecture, and has a huge impact on the entire development project. Developing components is therefore much more strategic than just developing components, and the basis of a approach in software engineering called component-based software engineering. (You should have a look at the article to get an idea about the complexities of this subject.)

Example: Airgate

Imagine we are the producer of airport gates, Airgate, like the ones we treated in the last unit. The airport gate consists of the hardware, that means, the turnstile, the display, the scanner and so on, and, of course, also the software. The software runs in the gate in an embedded computer, and connects all the hardware components together and integrates with the IT infrastructure of the airport, since we need to evaluate the validity of a boarding pass and register if a passenger boarded.

The software part of the airport gate makes up a large part of the system. Much of the system quality and hence value will depend on it working well, and we need to spend quite some effort to develop it.

Even though the functionality of the gateway seems simple, it has to take care of a long list of detailed requirements. Apart from the basic functionality that we already know, the gate has to log every passenger, allow for manual boarding, or take account for the central system being unreachable. Airgate is also selling many different configurations of airport gate.

- Different airports have different IT backends, and the system needs to integrate with each of them.

- Gates can have a different number of turnstiles and displays.

- There are different types of turnstiles, with slightly different logic that has been developed over time, since the mechanics change with improvements and local changes to the different airports.

Airgate does not only need a single software program that is the same on all their installations. Instead, almost all software installations are a bit different. How should this software be structured?

- A single program, a single file with instructions is a bad idea, simply because it is too complex. The different variants make it even more complex. I guess you agree this is not a good idea.

- Decomposing the software into different objects and classes is already better, but different objects here are too fine-grained. It would be very complicated to select the right ones for the right installation.

Instead, we decompose the software into a set of components, which itself contain classes, and code from different libraries. The components vary in size; some contain only little code or a few state machines, other may include larger code libraries and more logic. Deciding exactly how to structure the system into components is difficult and requires some experience, and we need to consider a lot of criteria that we will look at closer below.

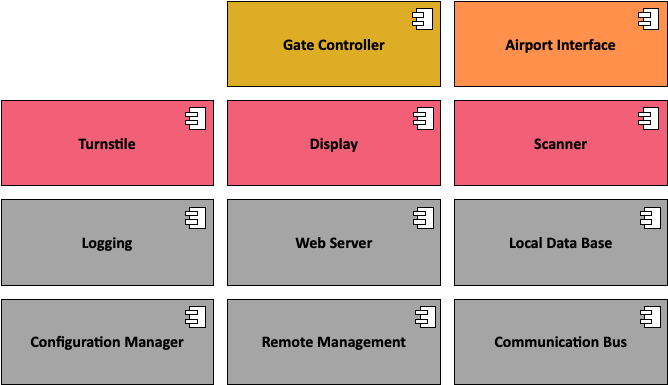

Component-based Software for AIRGATE.

To let you better understand, we show a diagram with components for the Airgate System below. We will later use these as examples.

- Gate Controller contains the main logic of the gate that ties together all hardware elements and the connection to the back end.

- Airport Interface contains the code necessary to adapt the Airgate System to different back-end systems, which makes it possible to use the Airgate System at different airports.

- Turnstile, Display and Scanner encapsulate all logic that is needed to adapt to the various versions of hardware Airgate has sold over time.

At the bottom of the diagram you see six more components, each providing more generic functionality. Most of them are from open source projects (such as Apache), because they are also used in many other systems.

- Logging provides a logging framework so that all events happening are logged into files or a data base.

- Data Base provides a database to store passengers passing for some time, in case the back-end system does not work.

- Configuration Manager is responsible for installing the proper component versions based on a configuration file and the specific hardware versions it detects.

- Remote Management offers a user interface so that operators can log into the software remotely and run diagnosis tests or change the configuration.

- Web Server contains a library to run a web server that is used by the remote management.

Modularity, Cohesion and Coupling

The main goal of introducing the system is to introduce modularity. With modularity we understand the degree to which components can be separated from each other and combined. High modularity means we can separate components easier from each other and combine them in different ways, resulting in higher flexibility and variety.

Looking at the components from Airgate, we can say that they have good modularity: A new version of the scanner can most likely be introduced by just adding a new version of the scanner module, and adding an additional module for a specific customer with some extra functionality also seems possible. Operations like these are much easier when we have good modularity, or can be a nightmare if we don't.

Good modularity can also be explained by a high cohesion of modules and low coupling between them:

- Cohesion means the degree of how much the functions of a component belong together. A component with high cohesion focuses on only a few things it does, while a component with little cohesion does a lot of different things.

- Coupling means the relation between several components. Ideally, this should be low, meaning that there is relatively little communication or dependencies between them. When there is a high coupling between two components, one should consider if it were easier to merge these two components into a single one.

You see that cohesion and coupling can be in conflict with each other: When we distribute some tasks between several components, we could end up with a high coupling between them, but highly cohesive components. When we, on the other side, combine these components into a single one, we could end up with a component that is not very cohesive because it does all kinds of things.

The Different Aspects of Modularity

Let's have a look in the following at the different aspects we have to think of when separating a system into components.

Units of Abstraction

Components offer a unit of abstraction, that means to structure the system and group different functions together. Ideally, when changing a detailed requirement, we only need to change a single component. Note that the last sentence start with the word ideally. While this is really the goal of good modularity, it's impossible to have such a good component structure that obeys this property for any kind of requirement changes.

But you can imagine that by structuring functions into suitable components, it is easier to understand the system, find the most likely point where changes are necessary or where errors may have their origin. It's a bit like sorting your hiking equipment into different boxes. It is probably not possible to pack your stuff for different journeys just by selecting a subset of boxes, but you have gained a lot of order once at least all the cooking stuff is in a box separate from the skiing equipment.

Units of Locality

Usually, a single component is located within a single computer that means, at a single location. It would be technically possible to run code belonging to the same component on distributed computers connected by a network, but this often requires more communication between these parts and makes the system more fragile. Instead, components should be physically concentrated.

Units of Delivery

Components can be a unit of delivery, that means, a company could outsource the programming for a specific component, or give separate components to separate departments or programmers. Likewise, in the semester project, you can give different team members to give the task for focus on the implementation of different components.

Single classes are often too small to be individual delivery items that are not worth the effort of ordering somewhere else, and often even classes cannot be developed by themselves because they are so closely coupled with other classes.

Components, instead, offer a unit that can be more suitable to deliver separately. For that, its interfaces and functionality must be described as precisely as possible for each component.

Units of Compilation, Deployment and Installation

New versions of components are often developed independently of each other, and therefore they are also separate units of compilation, that means, the process that generates some form of machine code from the source code and packages all files.

In OSGi for instance, all Java classes belonging to a single OSGi bundle are compiled and then placed together into a zip file which is then ready for deployment.

Deployment means that a component is made available on a platform, and maybe adjusted for specific settings. It is also analyzed if it has dependencies to other components that are required as well. The subsequent installation makes the deployed component available on a computer, and checks its integrity, for instance. (The detailed process depends on which kind of component framework we use.)

Units of Analysis and Understanding

Components also help to structure the system into parts that can be understood and analyzed separately from each other. Imagine for instance that you should create a new component for the turnstile, since there is a new one with slightly changed mechanics. You can have a look at the old component, see how it communicates with the other components (here probably most with the gate controller) and then develop a new version. Maybe you have to peek sometimes into some of the other components to find out a detail that is not documented as part of their interfaces, but having to focus on the turnstile component helps your work a lot.

Some requirements may also be so important that they require a deeper analysis to check that they really hold. An example would be the following requirement:

Only a passenger with a validated boarding pass may enter the aircraft.

This is kind of obvious, but where should we check if this requirement is fulfilled? We must analyze if it could open the turnstile even if it did not get an okay from the airport back end. This does not mean that we only need to analyze the gate controller, but this is where we can start and get an overview and then systematically check which other components are relevant for this requirement.

Units of Fault Containment

It's unrealistic to assume that software contains no errors. Sometimes errors do not show up even during extensive testing, but may be a combination of factors that only happen at runtime in a specific deployment. It's therefore good to have mechanisms in place that handle errors and can help to contain them, so that the effects for the system are less severe. Components represent such a possible containment border for errors. Internally, they must still be developed in a fault-tolerant way.

For instance, there could be an error in the Airgate system that leads to log files not being deleted as they should. Maybe the reason for this is even outside of the logging component, maybe because of some error in the configuration file for the file system or so. You see that it would be beneficial that the system could still operate and board passengers. This is possible if the error is contained within the logging component. For instance, the logging component detects the error when trying to write the file, warns the management system about errors, but does not cause the calling component (for instance the gate controller) to fail itself. Via the remote management, this error could even be temporarily mitigated by reconfiguring the logging component. If the whole system would be a single program, this would be more difficult.

Units of Testing

Testing is a comprehensive task, and tests need to be created at all levels of the system, and from many different views. For instance, there are tests for individual functions, and tests for entire use cases that span over several components. But components are a suitable scope to define test cases, too.

Units of Maintenance

Similar to components being developed independently, they can also be maintained one-by-one, that means, be the scope of improvements.

Units of System Management

Depending on the capabilities of the specific component framework that is used, components be a scope of system management. One could for instance see that one component should be replicated on several servers to do load balancing, or that some components should be moved to other machines.

Units of Reuse

All the aspects above make components also good candidates for being reused, that means, across several, possibly very different systems. The logging component, for instance, is so general that it can be reused probably in any system, while the Gate controller is probably not suitable for reuse, and certainly not outside of the Airgate product range.

In some situations, it may be smart to build a component with reuse in mind. However, this can also be dangerous, since it makes the initial development more expensive and shifts focus away on the specific system to build. There is always some uncertainty about if reuse will really happen, so there may be some overhead that in the end does not pay off. Therefore, be skeptical about the reuse argument in the first place.

Communication Between Components

Components can communicate with each other by various means.

- When components are written in the same programming language and execute on the same computer, they can communicate directly via method calls and passing data or objects between them, like different classes within the same program can communicate.

- Communication can also happen by a local message queue. This means that a component can send a message to another component. This allows for a more decoupled communication, i.e., the sender does not wait for the receiver and the message queue in between takes care of the delivery.

- Components may also use other means of communication, like an enterprise messaging system that also communicates between different locations.

This list of possibilities is not complete, and should just give you a glimpse of the vast number of possibilities there are.

In the Airgate system, for example, the Gate Controller uses a local messaging system to send and receive messages between Turnstile, Display and Scanner. (These correspond to commands like unlock, lock, etc.)

The remote management components use the web server functionality heavily and on a very fine-grained level, and therefore directly communicates via objects and method calls.

The airport interface uses an extra communication component that connects to the airport system. This communication component is responsible for serializing data into messages that are then transported via HTTPS and a more comprehensive infrastructure.

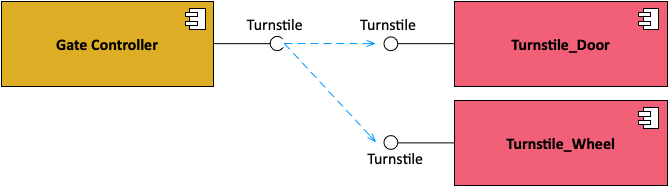

Components, Interfaces and Services

We have introduced above the idea that there can be different components for different variants of, for instance, the turnstile hardware. One cold be a turnstile that has a wheel, the other variant could be one with a little door. Imagine further that this has influence on the component directly interacting with the turnstile. We hence have two components managing the different variants of the turnstile; one for the turnstile with a wheel, one for the turnstile with doors. Their internal differences could be significant. The manufacturers of the turnstiles could use different wiring and communication buses. The turnstiles could also require different signals and different timing of them. That means, the state machines probably used inside the turnstile components could be very different.

For the logic inside the gate controller, i.e., the component coordinating the turnstiles, scanners, displays with the airport back end, these differences should ideally have no influence. It just requires that the turnstile can be locked or unlocked, and that it gives information if a passenger passed or not. With other words, it wants to know less about the details and just work with a more abstract form of the turnstile.

Interfaces

To make this work, both turnstile components should implement the same interface. The gate controller component can then use this interface to control the turnstile, without knowing which specific variant of implementation is hidden behind it. Depending on the technologies used, the interfaces can be defined in different languages, covering different details.

- Interfaces could identify method signatures, like in Java, to describe which methods the gate controller can invoke on the turnstile components.

- Interfaces could also identify messages passed back and forth between gate controller and turnstile, like

lock,unlock,passed.

In UML, interfaces can be visualized with the symbols below; one indicates a required interface, the other one a provided interface.

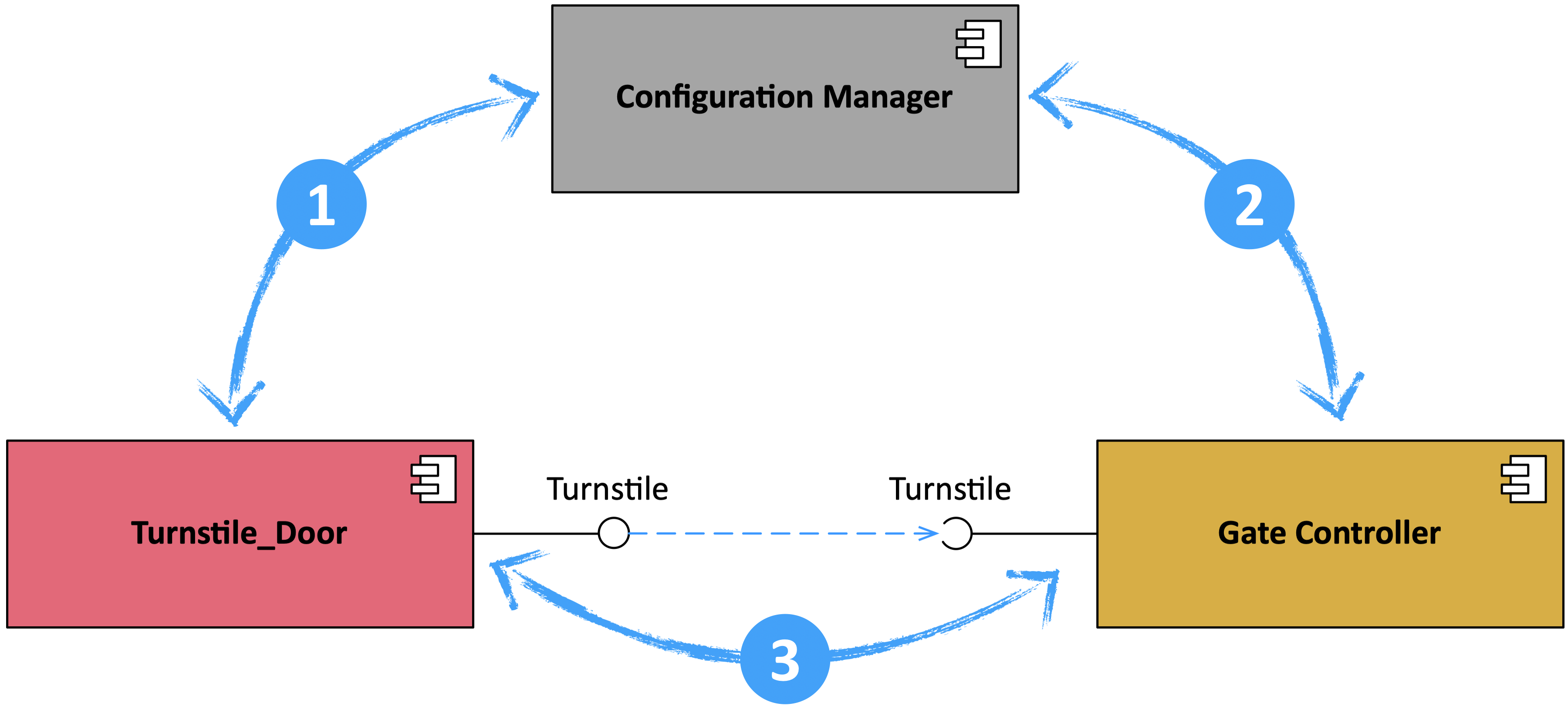

From Interfaces to Services

The interfaces describe how to use a specific functionality of a component. And indeed, in object-oriented programming, we can use these interfaces to plug together system parts. To make this also work in a component-based setting and in a dynamic way, we introduce the concept of a service. Have a look at the three-step interaction below:

- Service Registration: A component offering a service, such as a turnstile, first registers its capability in a service registry. In the example, the configuration manager could be the service registry that keeps an overview of all services available.

- Service Discovery: A component requiring a service, like the gate controller needs a turnstile, looks up which turnstiles are available by asking the service registry. As part of this discovery, it somehow needs to describe what it is looking for. In the simplest case, this can be some identifier of a service.

- Service Usage: Once the user of a service got a reference to it, it can use the service, as if they had been linked statically.

For this to work, we not only need a description of the interface, the interface only describes how a specific function can be used (which methods to use, which messages to send). The description of a service hence contains such an interface description, together with information on any dependencies, and also a description of what the service is providing. Loosely speaking, the service description is towards components about the same as an interface relative to a class in object orientation.

Services are the main way to structure modern systems, though in various forms and details. Services are the basis for many architectural styles. One of them is called SOA - Service-Oriented Architecture, and another one is that of micro-services. However, you should know about the principles so you can understand the idea, independent of a specific style or hype.

Component Frameworks

Most programming languages don't have support for components built-in. Java, for instance, has the concept of a package that can group together classes. A similar mechanism of modules and packages exist in Python. But such mechanisms are only part of what we need to have a complete component framework to manage them and have a flexible system architecture.

Instead, component frameworks are often defined separately, and contain rules for components (the so-called component model) as well as libraries that offer support for various component mechanisms. There are many examples, for different programming languages and different needs. Some component frameworks are commercial, some are open source.

In Java, for instance, OSGi is a packaging mechanisms that defines so-called bundles that are like a container for Java classes. These are effectively zip files with additional files internally that tell the OSGi runtime what to do with them. Based on OSGi there are at least three different component models (iPOJO, Blueprints, Declarative Services) that offer the concept of services.

Sun, the original company behind Java, also defined a component model for enterprise software, called Java EE (Java Enterprise Edition), which defined components separately from the Java language, as its own library and product.

Similar frameworks exist for many other languages. You can look at the (messy) list provided on the Wikipedia article on component-based software engineering to get a more complete picture.

The list of features is also long.

- Lifecycle management: Components need to be installed, started, stopped. The component framework implements such lifecycle functions.

- Service registration and discovery: A component framework can offer functionality to register services. The principle for that is simple, but the implementation can be complex.

- Persistence: Components may save their states and data when the computer is shut down, and the component framework can restore them at a later time. This function is called persistence.

- Communication: Component frameworks may also offer functionality for components to communicate with each other, and offer methods to manage channels and connections.

- Logging: Components may log events to make the monitoring of the system easier.

These are just a few examples of functionalities offered by component frameworks.